Did you know that French is the native language of over 200 million people? Because French has spread across five continents, it has evolved in many surprising and exciting ways. Our “French Around the World Series” highlights different variations of the language so that you can enrich your vocabulary and impress francophones with your in-depth knowledge of their culture. Check out our previous post about Swiss French here.

This week, we’re heading to the only region of North America whose official language is French: le Québec! Many of our New York students have visited Montreal, and a lot of them come back asking us why they had a difficult time understanding the French that’s spoken there. The thing is, although les français et les québécois use practically the same grammar and spelling, they speak with very different accents. Also, les québécois have pretty different vocabularies, as you’ll soon see.

Want to learn what differentiates Québécois from other forms of French? Tiguido!

By Sophia Millman

History of the Québécois Accent

You may already know that the French are slightly méprisant (disdainful) when it comes to Québécois accents. Parisians in particular might tell you that Québécois French is “distorted,” “incorrect,” “bizarre,” “hilarious-sounding,” or just “plain ugly.” But, in fact, Québécois is actually the purest version of French, historically speaking. Up until the 17th century, everyone in France spoke like the Québécois. Take that, you Parisian snobs!

Why is Québecois French more historically “correct” than standard Parisian French? Well, in a nutshell, the French explorer Jacques Cartier arrived in Canada in 1534. By the 16th century, Québec had been settled by colonists, most of whom came from North-Western France. They called this new region La Nouvelle-France or “New France.”

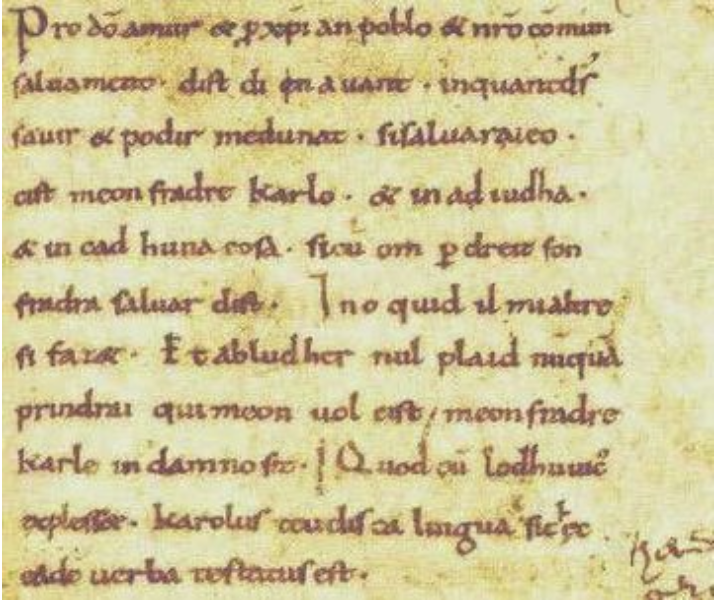

Now, this is where the split between France and “New France” becomes important: in 1763, the French Empire cedes its lands to the British and communication between Quebec and France is largely cut off. The people of Québec continue to speak old French. That is, they contract their syllables and consider many letters silent. In Paris, however, pronouncing words as they are written becomes more and more popular, and slowly Parisian French diverges from old French, while Québécois French stays the same.

Pronunciation Tips

As you might have noticed, in the image above, a lot of words have apostrophes in them. That’s because the Québécois love to contract words. Rather than saying, “À cette heure” like the French would, they say, “À c’t’heure” or “asteur.” Similarly, “tu sais” becomes “tsé.” Seems complicated? Don’t worry! We’ve broken down some of the important ways you can start changing your pronunciation if you want to talk like a true Québécois.

1. Contraction is key!

You may know that many French prepositions are contracted (de + le = du, à + le = au). Québécois has many more contractions: à + la becomes à’a (one long vowel). Sur + le = su’l. Also, les québécois rarely pronounce “il” as it is written. Instead they just say “ee,” which they write as “y.” For instance, when Parisians say “he is sick,” they say “il est malade.” Les québécois will say, “Y’est malade.” Similarly, instead of saying “elle as perdu ses clés” for “she lost her keys,” les québécois drop the elle and simply say, “A perdu ses clés.”

2. Lower the pitch of your voice

To master the Québécois accent you should lower your pitch by at least an octave! Les québécois speak in much lower tones than the French do, and they’re also supposed to sound more sing-songy.

3. Add S and Zs

In certain words, between the letters “tu” and “ti” les québécois add an S and between “du” and “di” a Z. For instance, “C’est dur à dire” (“It’s hard to say”) becomes “C’est dzur à dzire.”

4. Formulate your questions differently

When the French ask questions informally, they usually formulate them like this: “Tu m’écoutes?” (“Are you listening to me?”) But when les québécois asks questions, they tend to repeat the “tu.” So “Tu m’écoutes?” becomes “Tu m’écoutes-tu?” (Literally: “Are you listening to me, you?”)

5. Say Chu!

In your French classes, you’ve learned that Etre (to be) conjugated in the first person is “je suis.” But when les québécois speak quickly, they say “ch’suis,” “chui,” “chu” or even “ch’”! Example: “Je suis en vacances” (I’m on vacation) becomes “ch’t’en vacances.”

Common Québécois Expressions

French web developer Pierre Moreau launched his site “Je parle québécois” in 2015. When he first arrived in Montreal, he didn’t know anything about Quebec French, and was subject to many hilarious linguistic misunderstandings. So, he decided to create a project that would educate people about Québécois language and culture. While the site is in French, it’s an excellent resource for learning Québécois vocabulary and expressions.

We’ve picked out some of the most popular words and expressions you should master, as well as some of our personal favorites.

Attache ta tuque avec d’la broche: A very common Québécois expression. A “tuque” is a winter hat and a “broche” is a brooch or pin – or alternatively, haywire – used to attach the hat firmly to your head so it won’t blow off. This expression means to prepare yourself for difficulties ahead. Some say this expression was invented by Québecois folk-rock band Les Cowboys Fringants in their song “L’hiver approche”, rather than a traditional expression.

Breuvage: The typical word for beverage (rather than “boisson”). It refers to all beverages (sweet, sparkling, alcoholic or not) and is used everywhere–in restaurants, supermarkets and bars.

Char: When the French see this word, they think of Roman chariots or military tanks, but it actually means car in Québécois and is more common than “voiture.” Les québécois also say “chauffer un char” rather than “conduire une voiture” (to drive a car).

Écoeurer: A very common verb used in everyday speech. In addition to its standard French definition (to disgust), écoeurer means to annoy and to bore. Used as an adjective, écoeurant can mean both disgusting or delicious!

En masse: You might be able to guess the definition of this one! If you have a “masse” of something, you have a lot of it. This is a popular way of saying “beaucoup” in Quebec. Example: J’en ai beaucoup = j’en ai en masse (I have a lot of it).

Faque: This is derived from “fait que.” Widely used in Quebec, this term means “therefore,” “in fact” or “as a result” (donc, en fait, du coup). It is used to define a cause-and-effect relationship, but is so frequently said that it is sometimes used just to punctuate sentences rather than to provide a specific meaning.

Pantoute: The Québécois way of saying “pas du tout” (not at all). Example: Il n’en reste plus pantoute. (There’s none left at all.)

Plate: You’ll hear this all the time if you go to Quebec. It means both boring (ennuyeux) and disappointing/too bad (décevant/dommage). Examples: 1. Je trouve ce livre plate. (I find this book boring.) 2. C’est plate que tu sois malade! (It’s too bad you’re sick!)

Tiguidou: This is an amusing word used in everyday, more familiar language. It indicates enthusiasm and agreement. When you say “tiguidou,” it means something went perfectly well or that everything is in order. Other meanings are: good to go, perfect, great, and super. Examples: 1. “Mon boulot? C’est tiguidou!” (“My job? It’s awesome/going great!”) “Je suis tout tiguidou avec toi.” (I totally agree with you.)

Se tirer une bûche: This literally means “to haul oneself a log,” but it figuratively means “pull up a seat/chair,” or simply “to sit down.”

Et aussi:

Se faire passer un sapin: to get scammed

Ma blonde / mon cheum: my girlfriend/ my boyfriend

Tabernacle! / Ostie!: lots of québécois swear words actually come from religious vocabulary!

Famous Québécois

Céline Dion is by far the most famous French-Canadian celebrity, but there are plenty of others you should know about! To celebrate its 30th anniversary, the Canadian Encyclopedia created a list of 30 famous francophones from all corners of French-speaking Canada. Check it out here. A few of our favorite famous French-speaking Canadians include Guy Laliberté, the founder of Cirque du Soleil, and Michel Tremblay, a famous playwright who wrote Les Belles-soeurs. We also adore director Jean Marc Vallée, who has made many famous English-language films including Dallas Buyers Club, as well as one of the best Québécois films of all time: C.R.A.Z.Y. And, finally, we recommend that you watch the films of Montreal-born Xavier Dolan (see below)!

Tips for Learning Québécois French

If you want to learn more about Québécois language and culture, you should immerse yourself by watching French Canadian movies, listening to French Canadian music, podcasts or radio shows, and reading books by French-Canadian authors. Here are a few suggestions:

Movies:

Bon Cop, Bad Cop: Two police officers who are radically different (one is from Montreal and obeys the law, the other from Toronto and breaks the rules) are forced to work together to solve a mystery.

Incendies: This was nominated for an Oscar and is Denis Villeneuve at his best.

Monsieur Lazhar: Arguably the best Québécois film ever made, Monsieur Lazhar is about a substitute teacher who forms a close relationship with his students.

Other movies you should check out: Starbuck, C.R.A.Z.Y., Les Invasions barbares, and Xavier Dolan’s oeuvre (J’ai tué ma mère, Les amours imaginaires, Laurence Anyways, Mommy…)

Radio/Podcasts:

Radio Canada: Try “Ici Radio Canada Première” for news shows and if you’re interested in literature, we recommend “Plus on est de fous, plus on lit!”

Périphéries: Magnéto has a variety of excellent podcasts. This one is about stories that pass under the radar.

Avenir d’idées: This podcast is about innovative solutions to today’s social and political problems.

Books:

Mad Shadows by Marie-Claire Blais: Published under its original title La belle bête in 1959, this novel shocked Catholic Québécois readers upon its release with its gritty depiction of a dysfunctional family.

The Enigma of the Return by Dany Laferrière: Laferrière’s semi-autobiographical novel is about a Haitian émigré living in Montreal who must return to his native country for his father’s burial.

The Tin Flute by Gabrielle Roy: A story about familial bonds and survival during World War II, this classic novel won multiple literary awards and has been called the greatest Québécois novel.